| HOME | TRIBUNAL HOME |

December 1917

December 1917 marked one of the first real successes of the relentless political pressure that the NCF had exerted upon the civil government since 1916. As we saw in our November review, public opinion seemed to be building on the side of Absolutist Conscientious Objectors - not necessarily in sympathy with their position, but with the manner in which they were treated. December 1917 would mark both the 21st month of imprisonment for some men, but also the first legal admission that such treatment was not legal.

December 6th: What we stand for

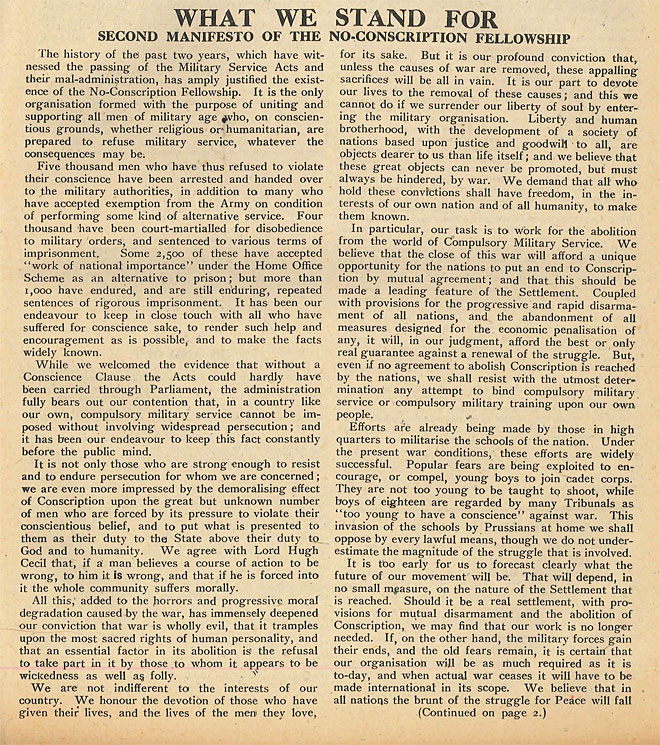

The leading article for the first December issue was a statement of policy and aims from the central committee of the No Conscription Fellowship, printed here as the “Second Manifesto”. In contrast to the 1916 manifesto, it does not only call for an end to the war and the release of imprisoned conscientious objectors, but is much more far ranging. By 1917 the NCF had grown and matured into a forward thinking political organisation, as concerned with the world to come after the war as with the fate of it’s members during it. The manifesto calls for:

Removal of the causes of war, for the benefit of all; pacifist or not

Work to abolish Conscription worldwide, during and after the war

Oppose the militarisation of education and the influence of the military in schools

Collective effort with all those opposed to war in order to bring about lasting peace

The manifesto bears a remarkable similarity to the efforts of many groups post war, and to the work of the Peace Pledge Union today. We are similarly dedicated to lasting peace, to a better and more peaceful world, to countering the influence of the armed forces in schools and to an end to conscription, both military and economic. This inheritance of ideas is no coincidence. From 1918 onwards, as the NCF began to look outward to the post-war settlement, it became clear that the focus on Conscientious Objectors would not last - necessitating a transformation into the No More War movement in 1920, later to merge with the Peace Pledge Union. In a very real sense, the Second Manifesto of the NCF was the ancestor of our work today.

December 13th: The Present Position

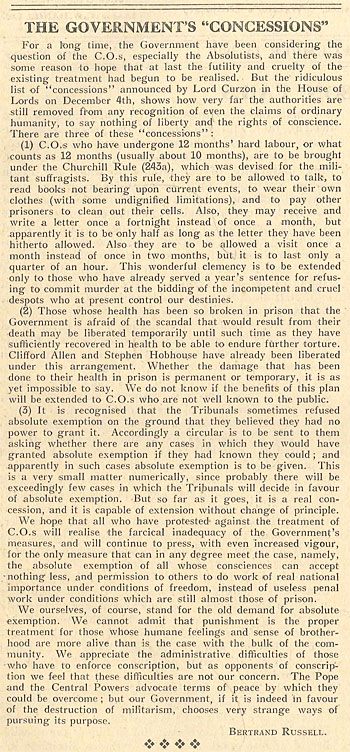

December 4th saw the announcement of concessions for imprisoned Conscientious Objectors, intended to both satisfy the general public and the anti-conscription movement. Such a broad (and largely contradictory) aim was unlikely to satisfy anyone, especially when the interests of the government - to appear tough on conscientious objectors, and refuse virtually any compromise - are taken into consideration. Bertrand Russell reported the concessions as a “ridiculous list”, believing them to largely be a cosmetic change to the fortunes of imprisoned COs. They read:

COs who had been imprisoned for at least 12 months were to be granted minor quality of life improvements. They would be allowed to talk, read books (provided they were not related to current events), potentially wear their own clothes and send and receive letters more frequently.

Critically ill Conscientious Objectors were to be temporarily released in order to recover their health outside of prison.

Tribunals were instructed to assess if “there were any cases in which they would have granted absolute exemption if they had known they could”, in order to reassess cases where absolute exemption should have been given. Russell dryly observes that “there will be exceedingly few cases” where this would apply.

Russell observed that these concessions were extremely minor - and did not balance out the debt owed by the state to those who refused “to commit murder at the bidding of the incompetent and cruel despots who at present control our destinies”.

The concessions, such as they were, were announced alongside a a major change in the rights of imprisoned COs. While gaining the right to read a wider selection of books in prison, they lost something far more critical: voting rights. Disenfranchisement of Conscientious Objectors was carried in the House of Commons on the 20th of November - but by a far reduced majority when compared to the passage of the Conscription Acts. The disenfranchisement was wide ranging, and would extend five years after the war ended. Most Absolutist COs would be formally stripped of their right to vote, as under the provisions of the act, all men who had applied for exemption as a CO and then subsequently undergone court-martial, would become ineligible to register or vote in Parliamentary and Local Government elections.

With one action, the government had shown the depths of it’s contempt for the Absolutist position. Passing minor (though in the case of the release of critically ill conscientious objectors, potentially lifesaving) reforms on the one hand - and removing all political rights on the other.

The final work on disenfranchisement in this issue of the Tribunal lies with Sylvia Pankhurst, noted suffrage campaigner, who “as a woman who would be enfranchised under this measure, I would rather wait till I can vote with all men and women on equal terms”.

December 27th: Arthur Butler

Though the release of ill conscientious objectors was now a legal possibility, COs would continue to die in prison and work camps until late 1919. Arthur Butler’s death was reported in the 20th December issue:

Arthur butler was educated at Stockport Grammar School, where he won a scholarship and gained the reputation of being a brilliant scholar. He was arrested in July 1916 as a conscientious objector. After his third sentence in May 1917, of two year’s hard labour for still refusing to obey military orders, he was committed to Preston Jail and here he developed consumption. In a letter from prison, dated November 10th 1917, he stated that he had a cough and spat blood and complained of pains in the chest and shoulders. The prison Medical Officer added a footnote to the letter stating that the spitting of blood was due to an acute attack of influenza, for which “he had every medical attention.”

Representations were made to the Home Office that Butler’s conditions was exceedingly serious, especially in view of the fact that a number of his family had died of consumption. But the Home Office persisted in stating that Butler was only suffering from a slight indisposition, and even as recently as 11th inst. assured a prominent member of Parliament that there was no cause of anxiety.

On the same day news reached Butler’s friends that he was dying. The Home Office was again approached, with the result that Butler’s mother was given permission to see him. But officialism had not yet finished it’s work.

While Butler, gasping for breath and fully conscious that his end was approaching, begged that his mother might remain with him, he was informed by the Governor that it was “against the rules.” Quite so, for what place have humanity, pity and sympathy within prison walls?

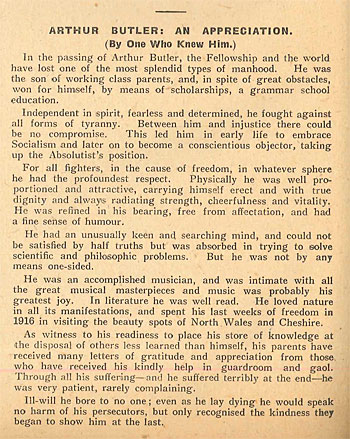

Arthur died the next day. As had become sadly common in the Tribunal, the announcement of his death was followed the next week by “An Appreciation”, and, as in all cases, it paints a picture of an inspiring man who had struggled until the end against war and militarism. More than that, though, it tells us of a kind a friendly man:

Ill-will he bore to no one; even as he lay dying he would speak no harm of his persecutors, bot only recognised the kindness they began to show him at the last”.

Arthur was the last CO to die in 1917, but by no means the last of the war. January 1918 would find many others in critical conditions, and the NCF scrambling to find the political leverage needed to have them released.

| more