| HOME | TRIBUNAL HOME |

November 1917

November 1917 - Public Opinion

After several quiet months of working at the coal face of Conscientious Objection, the end of October brought the NCF and the editorial staff of The Tribunal a thin ray of hope. Public opinion, usually hostile or at best indifferent of the plight of COs in prison, seemed to be turning. Perhaps due to the rumblings of revolution in Russia, or the increasingly terrible news from the slaughter at Passchendaele, the pointless waste, expense and continued imprisonment of men opposed to the war featured in major national press - and the NCF was eager to capitalise on this unexpected propaganda opportunity.

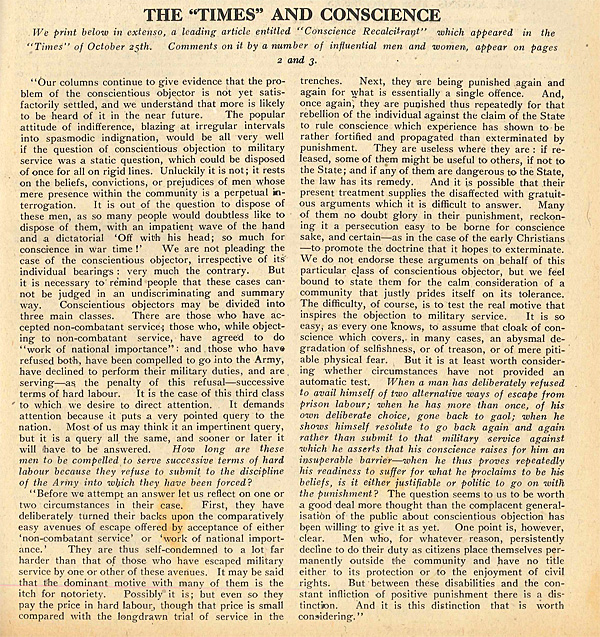

1st November: The “Times” and Conscience

Reprinted in it’s entirety from the editorial of the previous weeks Times (October 25th), this article presents the case for releasing imprisoned COs, from a non-pacifist perspective. Titled “Conscience Recalcitrant”, it levies the familiar charges of stubborn refusal, “an itch for notoriety” and the “cloak of conscience which covers, in many cases, an abysmal degradation of selfishness, or of treason, or of pitiable fear”, but tempers these accusations with the Times’ equally familiar conceit of objectivity. The article discusses the legality of punishing men for a crime that they both do not acknowledge and are willing to commit again and again.

By late 1917, some Absolutist COs were facing their third, or even fourth, prison sentence. Short sentences in the early days of Conscription had been served, and, after release, men found themselves again liable for call-up and inevitably returned to prison. The absurdity of this system and the waste of time, money and men that it inspired, was not lost on either the NCF or the Times:

“How long will these men be compelled to serve successive terms of hard labour because they refuse to submit to the discipline of the Army into which they have been forced?”

A question that “demands attention because it puts a very pointed question to the nation”, an acknowledgement that the NCF would have been happy to read, despite the qualifier that it was “an impertinent query, but it is a query all the same”.

It’s important to note that the Times article is not pro-CO or anti-war. It is fairly guarded and cautious, but still decidedly against the wider cause that COs stood for. It argues that they were “Men who, for whatever reason...place themselves permanently outside the community and have no title either to its protection or to the enjoyment of civil liberties”. But the point the article puts across is for the rule of law, and that the repeated punishment of Absolutist COs is neither “justifiable or politic”.

The legal argument regarding Conscription and Objectors is not one we focus on often, but many individuals, both CO and not, took up a position that the state had no right to conscript, or punish, men whose morality dictated that they could not go to war. Many of these people with a legal objection to Conscription were not anti-war, but instead drew from Britain’s historic respect for civil liberties and individual rights to argue that Conscription was a moral and legal crime. For the general public, the audience of the Times article, it’s likely that the argument offered, that repeated punishment of COs was unacceptable, was to be understood in this context.

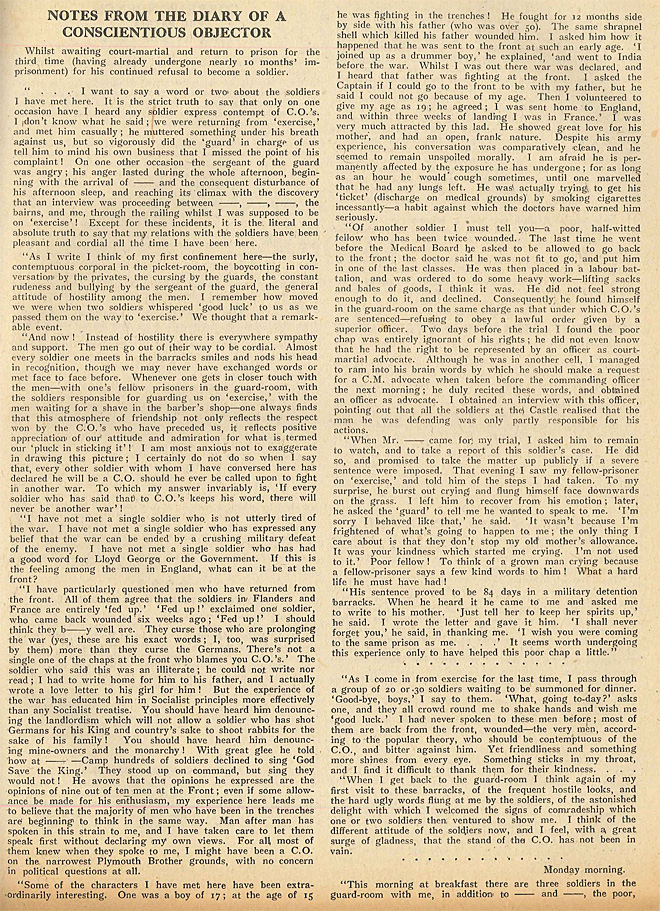

8th November: “Notes from the Diary of a Conscientious Objector”

In it’s next issue the Tribunal turns from the opinion of the general public to another supposedly bottomless font of anti-CO opinion, serving soldiers, to find a much larger swing in attitudes towards those who refused to fight. “Notes from....” is unsigned and the author is unknown, but reflects many other CO experiences in 1917 and beyond. The author writes from a barracks guard room while awaiting a second court martial, and from that, a second prison sentence, but remains remarkably upbeat about the process, allowing us to compare the broad attitudes of 1916 with those more than a year later.

He writes that his first guard room sentence was marked by “surly contemptuous corporal in the picket-room, the boycotting of conversation by the privates, the cursing of the guards, the constant rudeness and bullying... the general attitude of hostility among the men”, while his second shows “everywhere sympathy and support”.

Throughout the Tribunal’s print run, consistent small articles had highlighted acts of kindness from soldiers and letters of support, almost, but not quite, balancing out the frequent incidents of brutality suffered by COs around the country. This article is the first to suggest a general shift in attitudes beyond those evidenced by occasional good feeling. Respect had been “won by the COs who had preceded us” and “reflects positive appreciation of our attitude and admiration for what is called our “pluck in sticking it””, leading to a wider feeling of support and appreciation of the bravery of the CO position.

What had changed between 1916 and 1917 to produce this attitude? While the article hints at the presence of COs undergoing punishment in barracks around the country as a positive force for change, it’s likely that this was only a minor factor. War exhaustion and an appreciation for the reality behind the brutal, pointless grind of the western front probably contributed more to a general shift in attitude towards those who not only refused to fight on a personal level, but railed against the injustice of a system that forced men to war. The article states our anonymous CO had not “met a single soldier who is not utterly tired of the war”. For those transiting through barracks on their way to or from the front, it’s hardly a surprise to find a sympathy for, and even admiration of, a position that loudly states their pain and sacrifice was unjust.

Perhaps the largest factor in this change is one that isn’t acknowledged in the article. By November 1917, a CO in barracks would have been surrounded by a markedly different type of soldier than those he’d met the year before. Instead of professionals or volunteers, he would now have been meeting, on their return from their first or second time overseas, conscripts just like himself. Men who had been forced to fight, just as Absolutist COs were forced into prison.

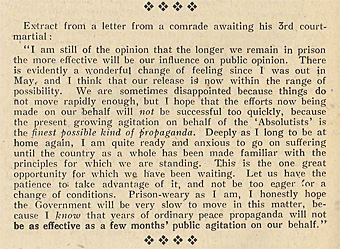

November 15th: Letter from a CO awaiting Court Martial

With public opinion in the pages of the Tribunal, some COs thoughts turned to ways of improving it and putting it to use for the pacifist cause. This letter, from a man about to go to prison for the third time, points out that the continued presence of Absolutists in prison, undergoing hardship and resolutely refusing to participate in the war made for powerful and undeniable propaganda of “the finest kind”. It shows a great deal of commitment to the cause, stating that “Prison-weary as I am, I honestly hope the Government will be very slow to move in this manner”, as keeping COs unjustly imprisoned allowed for constant campaigning for their release - a more effective tactic than “years of ordinary peace propaganda”. The dedication needed to trade potentially years of liberty for a chance to improve public perception of COs seems almost shocking today, but is in character for the Absolutist end of the CO movement.

November 29th: Peers and Prisoners

After a month of cautiously worded optimism that, with public and soldierly opinion behind them, COs could be freed of the monotonous cycle of release and punishment, Catherine Marshall’s report from the House of Lords brings back the uncaring reality of the Government’s approach to the Absolutists. Though prominently featuring an impassioned speech by Lord Parmoor focusing on his nephew, Stephen Hobhouse, then suffering through his second spell in solitary confinement, it is Lord Derby’s response that sums up the often fruitless struggle for justice that COs and the NCF faced.

Though Parmoor, supported by Lord Bryce had made the case for the release of COs undergoing successive terms of imprisonment, Lord Derby’s response is one of confusion, misconceptions and perhaps deliberate attempts to obscure the issue. He cited government and army regulations to indicate that COs in prison were under the jurisdiction of the Home Office for committing civilian crimes (a lie), that the Central Tribunal after hearing a CO in prison, could grant absolute exemption (impossible under the regulations of the Tribunal), and that men on the Home Office Scheme had never been under the control of the Army, absolving the military of any role in the situation (again, a bald lie).

This response could almost be used as a masterclass of political manoeuvring - firstly, blame someone else’s department, then claim a non-existent solution to the problem was already in place, then state that the problem was never your fault to begin with, and then (checking up in Parliamentary records confirms), refuse to answer further questions and leave the chamber.

It seems to have infuriated Catherine Marshall, who rounded on the broken promises made by Lord Derby and his predecessor as War Office spokesman to the House of Lords. Both had promised “no successive sentences”, and subsequently done nothing to ensure that this was the case. Marshall calls for both a confirmation of this statement from another source and for some means whereby “the War Office cannot be allowed to make definite statements of this kind, and then repudiate them”. Though she ends the article with “great faith in the results of an awakened conscience”, this must nevertheless have been a disappointing end to a promising month.