| HOME | TRIBUNAL HOME |

October 1916

While The Tribunal sometimes seems dominated by the same few writers, our look at the October 1916 issues shows that the variety of different voices that contributed to the paper and the CO movement as a whole. While the central committee of the No-Conscription Fellowship produced thousands of articles throughout the war, the paper frequently published letters, transcripts of court cases, interviews and lectures the NCF had received that explored different experiences of what it meant to be a CO, a pacifist or even a soldier during the First World War.

5th October - Fighting and Thinking

The last few months of looking at The Tribunal have usually avoided the headline articles, but the 5th October issue is an exception. “Fighting and Thinking” was written by Agnes Maude Royden, a suffragist, pacifist and secretary of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FoR). In 1914, she had split with Emmeline Pankhurst’s National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) over her pacifist views and went on to become the vice-president of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF).

The article is in many ways similar to other front-page Tribunal articles in it’s discussion, aims and audience. What set it apart from the crowd is it’s focus on the views and actions of “non-combatants”. Not, in this case, COs, but people who could not be combatants even if they wanted to - especially women.

Maude lays out core arguments for peace in a clear and concise way:

“‘You do not stop to argue’ someone said to me ‘when your house is on fire’ True, but If I saw some well meaning person hastening to put out the conflagration with a barrel of oil and a box of matches I think I should stop and argue with him”

and

“‘While people are throwing up earthworks in Kent’ said one to me, “it hardly seems the time to be discussing international arbitration.’ The point I want to drive home is that it is exactly the time to consider all questions of war and peace”

are well put points that, unlike many headline articles relating strictly to the First World War, relate to the conflicts of today as much as they do those of 1916.

The end of the article perhaps expresses some of the frustrations of women who saw their pacifism sidelined and excluded by a chauvinistic militarist political system and it certainly foresaw the attitude that would become the majority one by 1918:

“We owe it to those who have made the supreme sacrifice, to labour that it shall not be asked again We cannot go, some for physical, some for ethical reasons. But since those who do go suffer so much, and for their suffering we are all responsible, we are bound to see that, if it be possible, this war shall indeed end in a permanent peace.”

In many ways, the article is a rallying call to those who are not directly involved in the CO movement - and as Maude says “all non-combatants, especially women” - that they can do useful work for peace, and one that resonates strongly with the work we do here at the PPU.

12th October - The Australian N.-C.F.

Australia was the only major Allied country that did not introduce Conscription during the war, partially due to the concerted action of anti-conscriptionists who defeated attempts to impose it via referendum not once but twice! This letter sent to the NCF from it’s Australian equivalent shows that the same methods were being adopted by anti-conscription activists in both countries:

adopted by anti-conscription activists in both countries:

“Miss Grant is holding meetings at the street corners and the factory gates daily”

“the propaganda committee of the [Trade Union Congress] had a quarter of a million leaflets printed”

“Mr H. E Longridge has enthusiastically pushed the sale of the Labour Leader in Australia”

While a sadly familiar state-ordered campaign of repression swung into gear:

“I had been speaking for about ten minutes when the police ordered us off and arrested Grant for standing in the road”

“Mr Fred Holland has just been fined £15 and £8 costs or two months hard labour”

Most of the letter is very much a quick update on the progress of the NCF in Australia, which was going very well by mid 1916 by George Lilley’s account, but also to make contact between two beleaguered, unpopular and harshly repressed organisations. It’s a great example of the reality of COs belief that they were part of an international brotherhood and something that comes across in a lot of CO writing. Whether religious, socialist or objecting for personal ethical reasons, they were part of a group of people around the world in every belligerent nation who were standing up against the war, and I definitely agree with the end of the letter - “three cheers for International socialism and the No-Conscription Fellowship!”

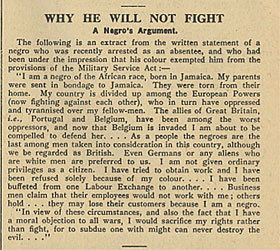

19th October - Why he will not fight

There aren’t many stories of COs from Commonwealth nations other than Canada and New Zealand, so “Why he will not fight” is a bit of a rarity in the pages of The Tribunal and poses a bit of a puzzle for the study of Conscientious Objection. The article is an extract from the court statement of a Jamaican CO who sees himself as African:

Conscientious Objection. The article is an extract from the court statement of a Jamaican CO who sees himself as African:

“My country is divided up among the European powers... who in turn have oppressed and tyrannised over my fellow men. The allies of Great Britain i.e. Portugal and Belgium have been among the worst defenders and now that Belgium is invaded I am about to be compelled to defend her.”

Arguments from COs about the First World War being an Imperialist war are not uncommon, but it’s rare to hear this perspective. The defence “Plucky Little Belgium” was Britain’s excuse for entering the war, but the country, by 1916 torn between the British and German front lines, was the owner of the Belgian Congo and was widely regarded as the most brutal, oppressive and segregated colonial regime. Why should any man actively fight for the right of Belgium to keep it’s colony, let alone a Jamaican well aware of the racist policies of the Belgian Congo?

His objection to war was also a personal one:

“As a people the negroes are the last among men taken into consideration in this country, although we are regarded as British... I am not given ordinary privileges as a citizen... I have tried to obtain work and I have been refused solely because of my colour”

Again, the question is clear - why should a man discriminated against, disbarred from working and faced with racism fight for the country which denied him the privileges other citizens enjoyed?

Aside from presenting a very different view of why someone should be a Conscientious Objector, the statement poses a bit of a puzzle for CO researchers - who is this man? It could well be Isaac Hall, who was a Jamaican CO who we first find record of in Pentonville Prison in 1917 where he had been refused even the scant privileges other COs received and, in the words of Alfred Salter had been reduced to “a living skeleton-a gaunt, bent, starved, broken man, a coal-black man with ashen lips and sunken eyes”.

But if Isaac is the man recorded here, he must have been sent to prison without Court Martial, without appearing before the Central Tribunal and without being made the offer of the Home Office Scheme, and remained in prison, illegally for several months. Isaac was eventually released and passage home was arranged through Alfred Salter and the NCF.

But was it Isaac who made the statement in this issue of the Tribunal? His objection to war has been recorded as based on his strong Christian faith and a belief solely that Christians should and could not kill. The man making the argument here is anti-colonialist and imperialist and doesn’t mention religion. The issue is racism and oppression - could it be a different objector? Was another Jamaican CO caught up in the machinery of Conscription?

26th October - What a Soldier Thinks

“What a Soldier Thinks” is a reprint of a letter that had appeared in The Nation a few weeks before describing a Soldier’s view on the public perception of the war. The Tribunal was always keen to publish the letters of soldiers at the front, partially as an example of the kinds of conditions and horrors that war brought, but also to highlight interesting opinions to open them up for wider debate.

“What a Soldier Thinks” is a reprint of a letter that had appeared in The Nation a few weeks before describing a Soldier’s view on the public perception of the war. The Tribunal was always keen to publish the letters of soldiers at the front, partially as an example of the kinds of conditions and horrors that war brought, but also to highlight interesting opinions to open them up for wider debate.

This article isn’t about conscientious objection but instead discusses propaganda - the image of the “smiling Tommy” that was used in both high and low propaganda in Britain throughout the war. A “veil of falsehood” has been drawn over the carnage of the western front that “flatters [non-soldier’s] appetite for novelty, excitement and easy admiration without uncomfortable emotional disturbance”.

The core of the letter concerns the perception of war on the home front. That the war was “ennobling and that men find in war the fulness of self-expression impossible in Peace, and that they are more truly men than when they were at home”. A century on, these myths still assault us and the perception that war is somehow a positive force in the lives of those that fight it is still a persuasive one. Resonating even more with the modern day, the statement that “men who have spent a winter in the trenches regard war with hatred, and hoping dimly that by suffering it now, they will save the future from it” is one that The Tribunal would have jumped at the chance to print and, more than that, delivers a stinging rebuke to those today who encourage and allow wars to be fought.