| HOME | TRIBUNAL HOME |

October 1917

While the September 1917 issues of The Tribunal focused on individual experiences, the October issues tell us far more about the priorities of the NCF - what was considered important and newsworthy. In many ways October was just another month of the struggle, but the final issue gives us some idea of the pressures the writers and publishers of The Tribunal were under.

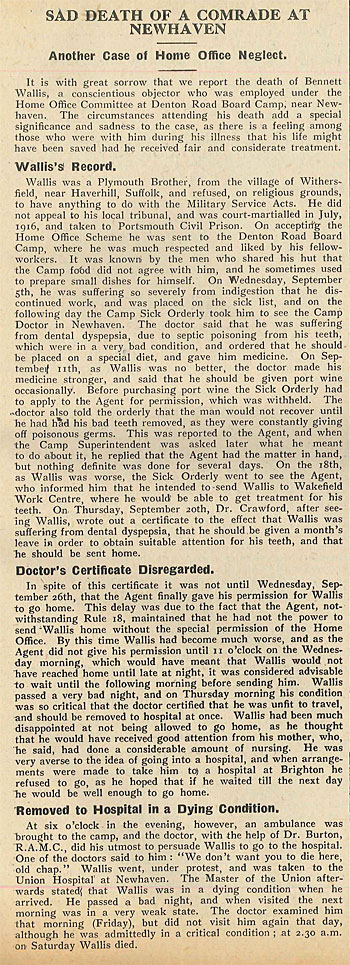

4th October - Sad Death of a Comrade at Newhaven

The month begins on sadly familiar ground, reporting on the untimely death of Bennett Wallis, a Plymouth Brethren CO on the Home Office Scheme at Newhaven. The Tribunal reported the d eaths of COs whenever they occurred with all the information they had available, but extra care and information was given to those sad cases where neglect, poor conditions and brutal treatment were to blame. Bennett Wallis died in the Newhaven Union Hospital on Saturday the 29th, seemingly due to septicaemia after developing dental infection.

eaths of COs whenever they occurred with all the information they had available, but extra care and information was given to those sad cases where neglect, poor conditions and brutal treatment were to blame. Bennett Wallis died in the Newhaven Union Hospital on Saturday the 29th, seemingly due to septicaemia after developing dental infection.

His experiences were published in The Tribunal at length, highlighting the by now familiar mix of incompetence, bureaucracy and malice that characterised so many deaths on the scheme. A slow and painful process - nearly a month - where Bennett’s health went from bad to worse, but a process that could have been arrested at any time had the HoS Agent simply allowed him to receive the proper medical treatment.

Though The Tribunal pulls it’s usual clear statement of responsibility, calling for an inquiry “not from any vindicitive desire to get anyone punished by in order that steps may be taken to safeguard the future of men in the Home Office Camps”, it is inconceivable that the delay between diagnosis and treatment was anything other than deliberate. With Bennett receiving permission to leave the camp for treatment on the 20th, the Agent withheld his leave until the 26th, in direct and deliberate contravention of rules laid down governing CO health and medical treatment. As a result, Bennett Wallis died.

Again, the Home Office Scheme was revealed to be a deliberately punishing and restrictive regime. If the Newhaven Camp was intended to get COs to do nationally useful work, why would the Agent withhold medical treatment from the men? The HoS toed the line between prison camp and work camp - and yet another CO death showed which side of the line the Newhaven camp could be found.

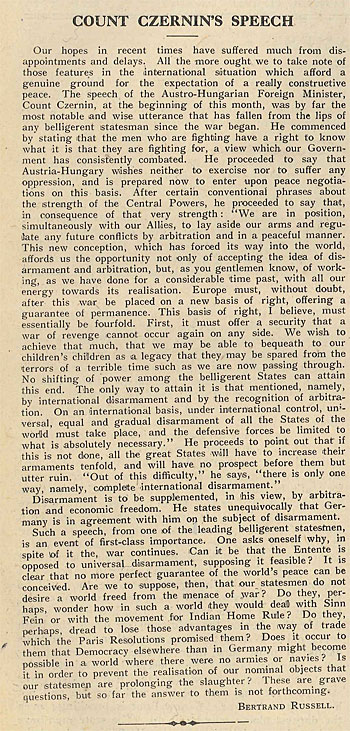

11th October 1917 - Count Czernin’s Speech

The Austro-Hungarian foreign minister’s early October speech must have appeared to the NCF as a thin ray of hope in an increasingly intractable and exhausting war. Czernin called for the belligerent nations to take basic steps towards peace and disarmament - echoing principles that had been a core part of The Tribunal’s arguments since the early days of 1916. Czernin stated that:

Soldiers should know why they are fighting, and honest statements of war aims should be made by all parties

Negotiated settlement could still be achieved

A settlement must be constructed so that wars of revenge could be averted

Nations around the world should take steps towards disarmament

Arbitration and economic freedom for all parties was a necessary part of maintaining peace

The Tribunal, quite rightly, called this “the most notable and wise utterance that has fallen from the lips of any belligerent statesman since the war began”. The article, written by Bertrand Russell, who by this point was writing the majority of leading articles and opinion pieces for The Tribunal, asks the very pertinent question - why was the Entente opposed to a negotiated settlement? Moving beyond the sunk cost fallacy that perpetuated the war and would eventually lead to the disastrous Versailles Treaty, Russell makes the point that the leaders of the Entente do not, and never did, want peace. A non-militarised Britain would mean freedom for India and for Ireland, less profit for the owning classes and democracy - far from the aims of those with a vested interest in carrying on the war.

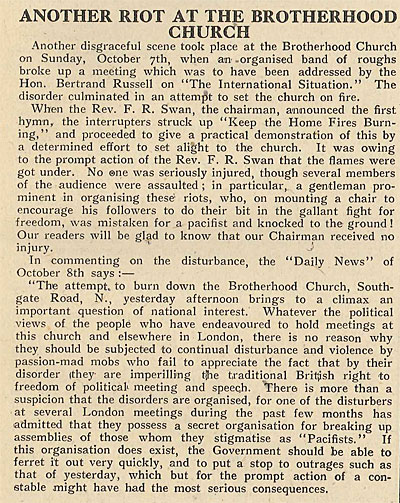

11th October 1917 - Another Riot at the Brotherhood Church

The Brotherhood Church was one of many hubs of CO related activity in East London. The church was on Southgate road and hosted talks, events and discussions on pacifism, left-wing politics and christian socialism. It’s support for the CO movement, and determination to continue that support in the face of all opposition, made it deeply unpopular and riots and disturbances were frequent - usually whipped up and orchestrated by the national press. This riot was more serious than the several other occasions on which meetings had been disturbed. While Bertrand Russell was speaking on “The International Situation”, a large group of men disrupted the meeting and attempted to set the church on fire. This was one in a long series of attacks on the church, and would almost be the last - not long after, a meeting would be successfully disrupted, several pacifists beaten and the church burned to the ground. As in all previous cases, the local police stood by.

The suspicion that these disruptions were arranged by a “secret organisation for breaking up assemblies of those they stigmatise as “pacifists”” as the Daily News put it, was likely not far wrong. Instead of a secret organisation, the right-wing press and Horatio Bottomley - once and future South Hackney MP, whose electoral campaign had been largely based on disrupting opponents - made no secret of wanting meetings disrupted, and widely publicised the location, date and time that they would be held in the church. Articles like this not only brought the news to the readership of The Tribunal, but also reminded them of the level of hatred and viciousness their cause could face - and encouraged them to be ready for it.

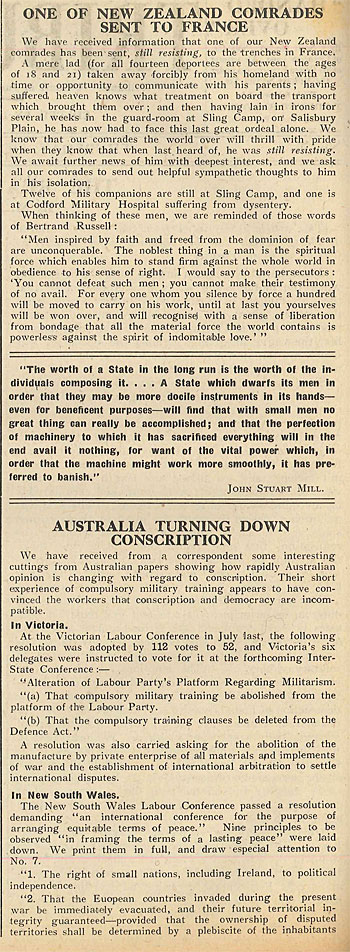

18th October - Australia and New Zealand

With the situation at home continuing to remain largely static, The Tribunal again turned to the international situation for news and developments on CO matters.

The saga of the New Zealand COs who had been sent to France had previously stabilised, with all fourteen of the men taken from France to England - there to exist in an uneasy limbo within Sling Camp on Salisbury Plain. This article, however, shows that the situation had again deteriorated and “A mere lad” had been taken from the camp and transferred, alone, directly to the trenches. The NZ COs who found themselves sent to France did spend time in the front lines and under attack, something that had not happened to any resisting absolutist British CO. The article is not only indignant that this could happen, but also defensive, the writer well aware of the stress of being separated from comrades in the movement. “We await further news with deepest interest” it reads, and “we ask all of our comrades to send out helpful thoughts to him in his isolation”. Alone and on the other side of the world, one CO was in the trenches, but, as The Tribunal crows “the last he was heard of, he was still resisting”.

In contrast to the situation in New Zealand, the Australian debate over conscription must have been a source of comfort and support for the British movement. Australian anti-conscriptionists had defeated a referendum calling for conscription almost a year earlier on 28th October 1916, and though the Nationalist Coalition government (how familiar a phrase that would have been to British COs!) were building towards a second attempt at passing conscription, the outlook did not appear to be in their favour. A wide variety of groups, from religious to socialist and trade unionist, came out against conscription, and the article prints news and opinions keeping the readership up to date on new developments in the Australian movement.

Updates from Australia were common in the pages of The Tribunal during the quiet months of 1916 and 1917. Far from an editorial scramble to fill space, though, this was a calculated morale boost. The defeat of the Australian conscription bill at the ballot box was not just news, but a reminder that anti-conscription arguments could be taken in front of the general public, that groups just like the NCF could take on the government, and win.